Iran has the largest deposits of hydrocarbon resources in the world, with the world’s biggest proven gas reserves (34 Tcm or 1,200 Tcf) and the fourth largest proven crude oil reserves (157.8 Bbo). Due to the imposition of sanctions, over the last few years Iran has not been able to invest adequately in its upstream sector – the official figures suggest an average of $3 billion/year over the last three years. However, since a comprehensive deal on sanctions was finalised on 14 July 2015 and the prospect of foreign investment has become a reality, there has been significant interest from foreign E&P operators and service companies.

What’s on Offer?

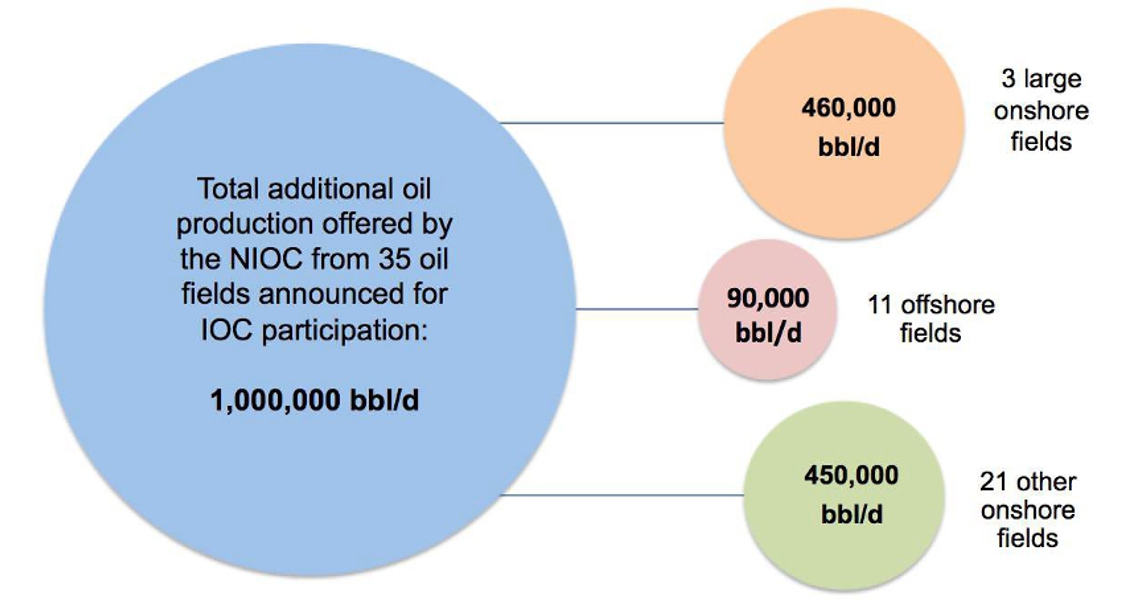

Iran is offering 70% of its untapped oil and liquid reserves from a range of green and brownfield projects. The National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) presented 51 upstream E&P projects for foreign participation during the Tehran Summit on 28 November 2015. In total it is estimated that these fields could add over 1.28 MMbopd – probably a conservative estimate – and 8 Bcfgpd to Iran’s production.

To facilitate this, in 2013 the Iranian government embarked on an unprecedented overhaul of the contractual regime. The new Iranian Petroleum Contracts will offer significant incentives to IOCs over the previous buy-back contracts, including:

- Longer contract horizon (20–25 years)

- Appointment of the IOC as ‘Operating Manager’

- Development fee per barrel linked to the market price of oil

- Alignment of interests for all parties to encourage long-term collaboration

Through the new contracts NIOC is seeking to encourage participation from IOCs to address gaps in the local Iranian market. They hope they will bring in advanced technologies, including those used for IOR and EOR in order to improve or maintain recovery in existing fields and reduce gas injection in oil fields, a commodity Iran is looking to export. The NIOC also expects participating companies to introduce the latest technologies in use in heavy oil fields, deep reservoirs and sour gas fields, and innovative methods for reservoir management and optimisation as well as surface asset integrity management.

A number of the smaller fields on offer, with production in the range of 3–5 Mbopd, will require lower CAPEX investment, which should encourage smaller and medium sized IOCs to enter the Iranian market.

Based on analogous costs in the neighbouring Kurdistan region of Iraq, the break-even costs of Iranian onshore oil fields could be $20–35/bo, with a lifting cost of $4.5/bo. Assuming sanctions are lifted in the expected time frame, a conservative estimate of $30 billion can be made for the upstream investment into development projects out to 2020.

Why So Much Oil?

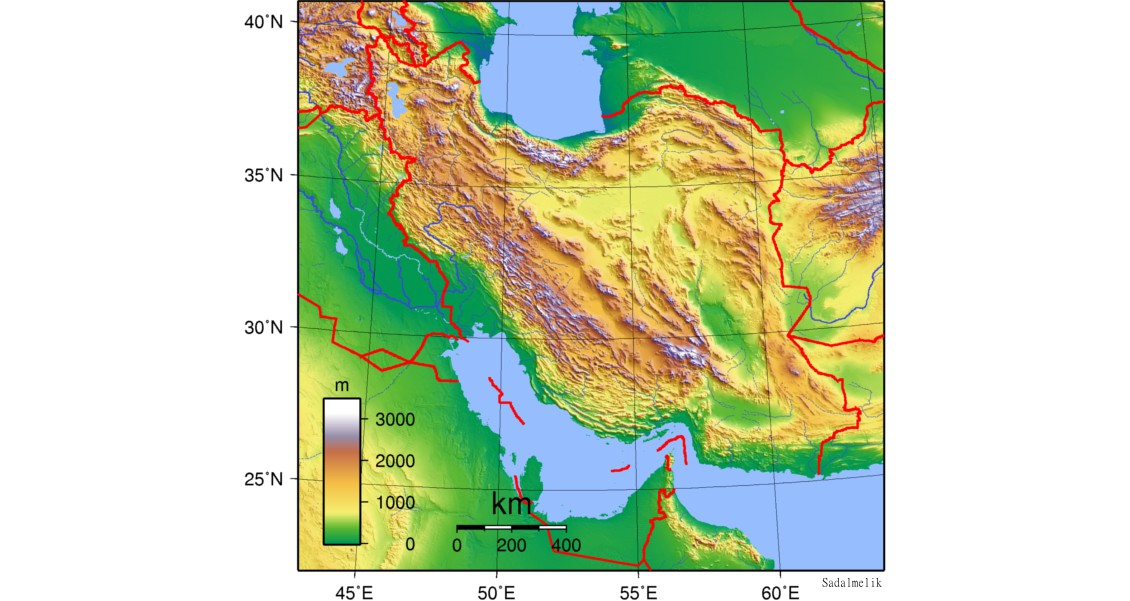

Iran can be divided into several tectono-sedimentary zones, all of which have been investigated for hydrocarbon potential by regional geological studies and through drilling exploration wells.

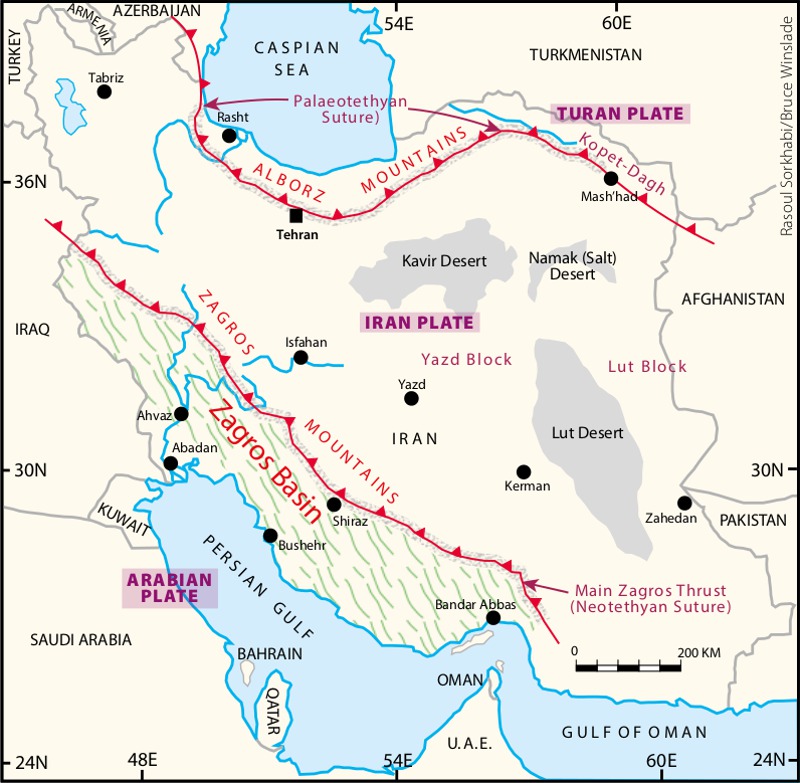

Structural zones of Iran. (Source: Rasoul Sorkhabi/Bruce Winslade)The first oil discovery in Iran was in the Zagros Basin in the Masjed-Soleyman area in 1908 and until 1956 it remained the sole petroleum region in the country. Oil was discovered in the Alborz anticline in Central Iran in 1956, and the first hydrocarbon discoveries in the north, though deemed to be uneconomic due to low permeability, were in the 1960s, when large gas fields were also discovered in the Kopet-Dagh Basin in north-west Iran. However, most of Iran’s reserves are located in the Zagros, which remains the most prolific basin in the country. (For more on the history of oil exploration in Iran, see the section ‘Further Reading’, at the end of this article)

Structural zones of Iran. (Source: Rasoul Sorkhabi/Bruce Winslade)The first oil discovery in Iran was in the Zagros Basin in the Masjed-Soleyman area in 1908 and until 1956 it remained the sole petroleum region in the country. Oil was discovered in the Alborz anticline in Central Iran in 1956, and the first hydrocarbon discoveries in the north, though deemed to be uneconomic due to low permeability, were in the 1960s, when large gas fields were also discovered in the Kopet-Dagh Basin in north-west Iran. However, most of Iran’s reserves are located in the Zagros, which remains the most prolific basin in the country. (For more on the history of oil exploration in Iran, see the section ‘Further Reading’, at the end of this article)

Tethyan Ocean evolution shaped Iranian geology and its tectonic style, resulting in the generation of prolific petroleum systems.

Iran was on the northern margin of Gondwana until Devonian times, when extension resulted in rifting and the creation of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean and the separation of northern Iran from Gondwana (Boulin, 1988). During Carboniferous to Permian times another extension phase in northern Gondwana resulted in the creation of the Neo-Tethys Ocean. By the late Triassic this had reached its maximum extension and the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean had closed. The majority of Iranian oil and gas reservoirs in the Zagros Basin were deposited in the margins of this new ocean.

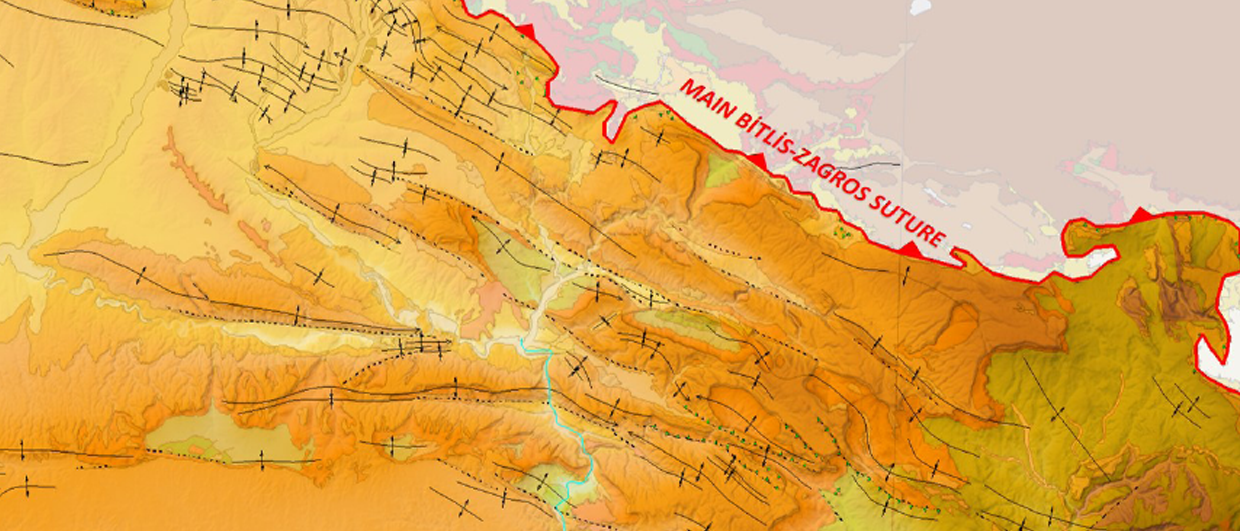

From the Jurassic to early Tertiary, the Neo-Tethys Ocean underwent subduction as the Arabian plate collided with Eurasia, creating major structural traps in the Zagros area, including many large, hydrocarbon-filled anticlines in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, primarily trending north-west to south-east. A few structures exhibit a north-south trend due to movement of the basement faults (Steineke et al., 1958).

At various times passive margins with extensive carbonate platforms developed along the Tethys Ocean, creating high quality reservoir rocks in the Zagros Basin. In addition, intrashelf basins formed during vertical movements of rift blocks, and important source (Garau Formation) and evaporate cap rocks (Hith Formation) were deposited (Pratt and Smewing, 1993).

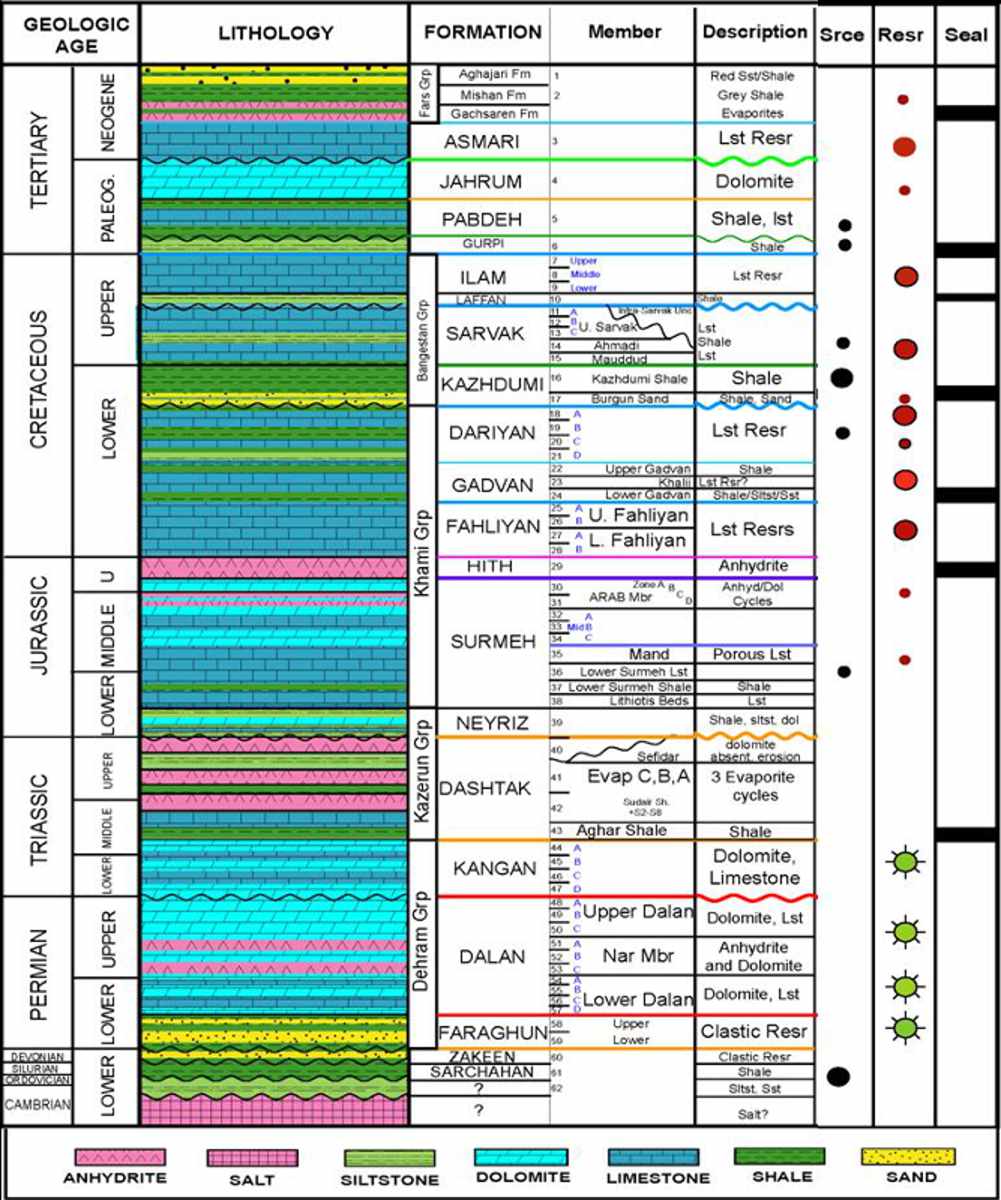

Relative sea level change caused by tectonic movements and climate change resulted in the depositional cycles which are responsible for the creation of the prolific petroleum systems found in the Zagros Basin. Organic rich shales were deposited during sea level rise, followed by prograding carbonate deposition during highstand times. Cap rocks were created either by continental deposition during lowstand or as marine deposits of the next cycle. There are multiple petroleum systems in the Zagros Basin as a result of this cyclical deposition. (Note that nomenclature and correlation of strata vary in each area of the basin.)

The most important source rocks are the Sergelu, Garau, Kazhdumi and Pabdeh Formations. The significance of each varies from area to area within the Zagros – and sometimes source rocks change laterally into reservoir rocks.

Summary of Main Reservoirs

Over 90% of the hydrocarbons in the Zagros Basin are found in carbonate reservoirs, with oil accumulating in Mesozoic and Tertiary rocks, while most gas is in Permian and Triassic reservoirs. In the majority of discoveries, hydrocarbons are trapped in the anticlines; no stratigraphic traps have yet been discovered.

Almost 85% of Iran’s crude oil is produced from the Oligo- Miocene Asmari Formation, with 59 Asmari reservoirs (51 oil and 8 gas) having been found in the Zagros Basin. The main producing section is 330–500m thick, although in some fields – for example, Gachsaran – the vertical difference between spill point and the crest can be nearly 2,000m. The evaporates of the Gachsaran Formation provide a thick and efficient seal to the Asmari reservoirs.

Almost 85% of Iran’s crude oil is produced from the Oligo- Miocene Asmari Formation, with 59 Asmari reservoirs (51 oil and 8 gas) having been found in the Zagros Basin. The main producing section is 330–500m thick, although in some fields – for example, Gachsaran – the vertical difference between spill point and the crest can be nearly 2,000m. The evaporates of the Gachsaran Formation provide a thick and efficient seal to the Asmari reservoirs.

The Asmari Formation is not all carbonate. The Ahwaz Sandstone, for example, is an important and extensive member of the formation, up to 249m thick. Asmari lithology can be a mixture of dolomite, limestone, anhydrite and shales interbedded with the Ahwaz Sandstones.

For the newcomer to Iran, it is interesting to note that Asmari reservoirs typically have moderate to high porosity (12–24%), particularly high in the Ahwaz Sandstone Member, and extensive fracturing systems, with high reservoir pressure and moderate to high aquifer water drive. They contain good quality crude oil with low H2S content and light gravity oil (API >30°), often in giant geological structures, and their shallow depth of burial means low-cost drilling.

Giant fields producing from the Asmari Formation include Maroun, Gachsaran, Aghajari, Karanj, Mansouri, Koupal, Bibihakimeh and Masjed Soleyman.

The second largest reservoirs are the Middle Cretaceous Bangestan Group, producing from Ilam, Sarvak and Kazhdumi Formations. They are capped by the thick Pabdeh/Gurpi marls in most areas of the basin. Bangestan reservoirs are deeper than Asmari oness, making them harder to drill and produce. As the reservoir rocks are generally dense with low to medium porosity and permeability, the primary recovery factor is low, and they have a weaker water drive than Asmari reservoirs. IOR and EOR methods have therefore been proposed, including hydraulic fracturing and massive acid treatments.

The common characteristics of Bangestan reservoirs are huge geological structures bearing high oil volumes in dense limestone and dolomite reservoir rocks with low to medium porosity. Asphaltene is found in some reservoirs.

Bangestan Group Formations are the main oil reservoirs in the Azadegan, Abteymour, Yadavaran, Jofeyr, West Paydar and Binak fields, and secondary producer in many fields, including Ahwaz, Gachsaran, Bibihakimeh, Mansouri, Rag Sefid, Koupal and Soroush.

The Middle Jurassic – Middle Creataceous Khami Group, which includes the Dariyan, Gadvan, Fahliyan and Surmeh Formations, usually contains oil or gas condensate fluids, sealed mainly by the Gadvan Formation. There are a limited number of these reservoirs, which are located at low depths up to and beyond 4,500m subsea, so they require advanced drilling and completion practices. Khami reservoirs have high initial reservoir pressure and contain some H2S gas. The main Khami reservoirs are located in the Gachsaran, Khaviz, Arash, Darquain and Garangan fields.

The Dehram Group includes gas reservoirs in the Early Triassic Kangan and Permian Dalan Formations, making the latter the oldest reservoirs in the Zagros Basin. They are composed of dark limestones and dolomites and capped by Dashtak and Nar evaporates. The dolomitised oolitic carbonates of the Kangan Formation exhibit enhanced porosity due to diagnetic process. Despite having a major unconformity between the two formations, they are hydraulically connected and thus make one reservoir unit. The best example of this reservoir is the South Pars gas field in the Persian Gulf.

Time for Iran?

The presence of thick depositional sequences with good quality source, reservoir and cap rocks and suitable structures have made the Zagros Basin one of the most prolific petroleum basins in the world. Iran, and in particular the Zagros, has multiple petroleum systems and a long production history, suggesting therefore, that it has a very high geological chance of success. Coupled with the improved contracts and a large number of expert Iranian companies looking to partner with outside companies, maybe it is time to take another look?